When we think of rocks, we often imagine solid, unchanging chunks of Earth. But the truth is, rocks are constantly evolving, especially under the surface where heat and pressure shape their identity. One of the best ways geologists understand the metamorphic journey of rocks is through a concept called metamorphic facies.

Let’s unpack what that really means and explore the fascinating world of metamorphic facies and what they reveal about Earth’s dynamic interior.

What Is a Metamorphic Facies?

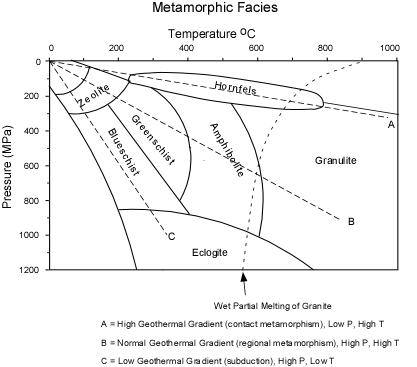

In simple terms, a metamorphic facies is a set of mineral assemblages (groups of minerals) that form under specific conditions of temperature and pressure. Each facies represents a certain environment deep within the Earth where rocks were transformed.

Geologists use facies to decipher the pressure-temperature (P-T) history of rocks, which helps in reconstructing tectonic events like mountain building, subduction, and crustal thickening.

Why Do Metamorphic Facies Matter?

Each facies acts like a geological fingerprint. By identifying the minerals in a rock and matching them to a facies, geologists can tell how deep the rock was buried, how hot it got, and what kind of tectonic environment it came from, whether it was dragged into a subduction zone, squeezed in a mountain belt, or baked next to a magma body.

It’s not just about naming rocks, it’s about telling their life story.

The Main Types of Metamorphic Facies

Zeolite Facies

Temperature: ~50–200°C

Pressure: Low

Mineral assemblage: Zeolites (e.g., laumontite, stilbite), chlorite, quartz

Where It Forms: This is the gentlest metamorphic environment—often just a step above regular sedimentary diagenesis. You’ll find it at shallow depths in basins or the early stages of burial metamorphism.

Rocks here haven’t been under much stress. They’ve experienced just enough heat and pressure to form new minerals, but not enough to fully recrystallize.

Prehnite-Pumpellyite Facies

Temperature: ~200–350°C

Pressure: Low to moderate

Mineral assemblage: Prehnite, pumpellyite, chlorite, albite

Where It Forms: Transitional between low-grade burial and regional metamorphism. Often seen in oceanic crust that’s beginning to be subducted.

A sign of rocks starting to feel the squeeze. They’re not fully metamorphic, but the mineral makeup shows deeper burial and mild heating.

Greenschist Facies

Temperature: ~300–500°C

Pressure: Low to moderate

Mineral assemblage: Chlorite, actinolite, epidote, albite

Where It Forms: Common in collisional mountain belts and along continental margins. This is one of the most widespread facies in regional metamorphism.

Rocks in greenschist facies are undergoing classic regional metamorphism. Minerals are aligning, foliation begins, and the rock starts looking very different from its original form.

Amphibolite Facies

Temperature: ~500–700°C

Pressure: Moderate

Mineral assemblage: Hornblende, plagioclase, garnet, staurolite

Where It Forms: Found deeper in the crust, typically in orogenic belts where rocks are being buried and heated during mountain building.

Things are getting serious. The rock is undergoing recrystallization and developing larger, more visible metamorphic minerals. You’ll often find schists and gneisses in this facies.

Granulite Facies

Temperature: ~700–900°C

Pressure: Moderate to high

Typical Minerals: Orthopyroxene, plagioclase, garnet, sillimanite

Where It Forms: Deep continental crust, often in the roots of ancient mountains or high-grade metamorphic terranes.

These rocks have seen the most intense cooking without melting. They tell tales of deep crustal processes and ancient tectonic events.

Blueschist Facies

Temperature: ~200–500°C

Pressure: High

Mineral assemblage: Glaucophane, lawsonite, epidote

Where It Forms: Subduction zones, where oceanic crust plunges into the mantle. The high pressure and relatively low temperature create a unique set of minerals.

These rocks have been pushed deep very quickly, with little time to heat up. That’s why you see high-pressure minerals like glaucophane, a beautiful blue amphibole.

Eclogite Facies

Temperature: ~500–800°C

Pressure: Very high

Mineral assemblage: Omphacite (a pyroxene), garnet, kyanite

Where It Forms: Also in subduction zones, but even deeper than blueschist. Eclogites form at the boundary between the crust and the upper mantle.

Rocks in this facies are survivors. They’ve been subjected to extreme pressure and temperature, but some manage to return to the surface, offering rare insights into Earth’s deep interior.

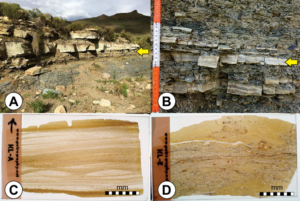

How Facies Are Identified

Geologists identify metamorphic facies by analyzing thin sections of rock under a petrographic microscope. They look for:

- Mineral assemblages

- Texture and grain size

- Zoning and reaction rims

Using phase diagrams and P-T stability fields, geologists match the observed minerals to a specific facies.