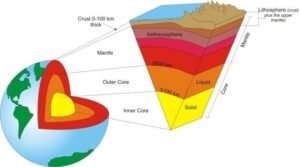

Plate tectonics is the unifying theory of modern geology. It describes the large-scale motion of Earth’s lithosphere—the rigid outer shell comprising the crust and the upper mantle. Imagine the Earth’s surface not as a static, solid carapace, but as a mosaic of gigantic, interlocking rocky plates, each slowly but incessantly on the move. This continuous dance, driven by heat from the planet’s interior, is responsible for shaping the world’s most dramatic landscapes, from the mightiest mountain ranges to the deepest ocean trenches, and is the fundamental force behind earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and the very evolution of our continents over billions of years.

The engine of this system is the Earth’s internal heat, which creates convection currents in the ductile asthenosphere beneath the lithosphere. Like a pot of soup simmering on a stove, hot material rises, cools as it nears the surface, and then sinks again, dragging and pushing the overlying tectonic plates along. These plates, which number about seven major and several minor ones, interact at their boundaries. It is at these plate boundaries where the geologic action is most intense, and they are classified into three primary types based on how the plates move relative to each other: divergent, convergent, and transform.

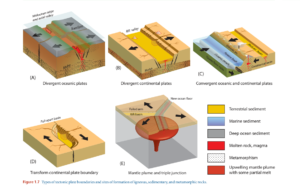

Divergent Plate Boundaries

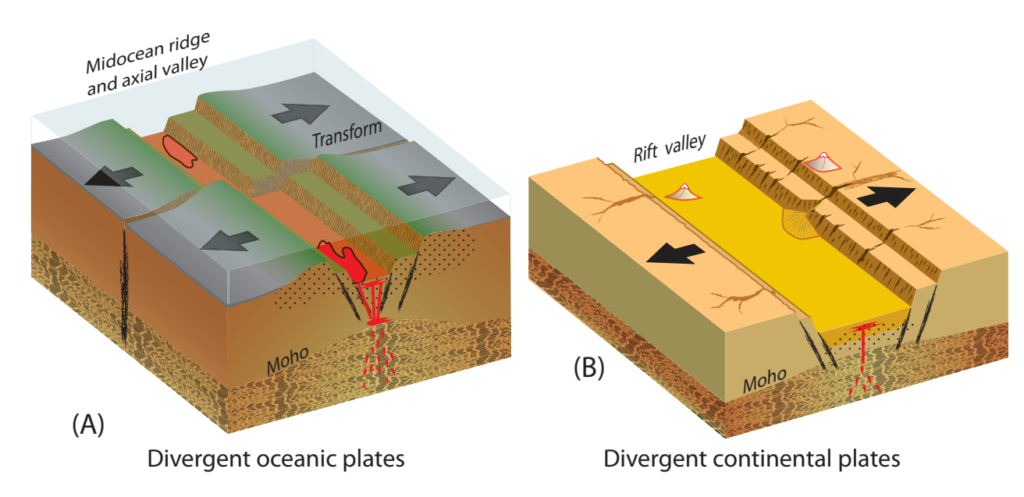

Divergent plate boundaries, also known as constructive margins, are locations where tectonic plates are moving apart from each other. As the plates separate, the reduction in pressure allows hot rock from the mantle to melt and well up into the gap. This magma cools and solidifies to form new oceanic crust, a process known as seafloor spreading.

The most iconic examples of divergent boundaries are the mid-ocean ridges, like the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a vast underwater mountain chain snaking through the Atlantic Ocean. Here, new oceanic lithosphere is constantly being generated, pushing older crust away on either side. On continents, divergent boundaries can rip landmasses apart, creating continental rift valleys such as the East African Rift System. Over millions of years, this rifting can lead to the formation of a new ocean basin. The geologic activity at these boundaries is characterized by frequent, but usually low-to-moderate intensity, earthquakes and volcanism from the upwelling basaltic magma.

Convergent Plate Boundaries

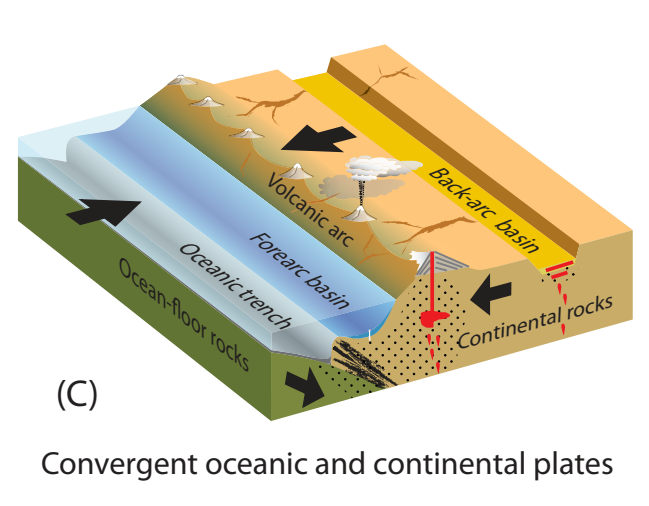

Convergent plate boundaries, or destructive margins, are where two tectonic plates move toward each other. This head-on collision is the most dramatic type of plate boundary, leading to some of Earth’s most spectacular and hazardous phenomena. The specific geologic features depend on the type of crust involved in the collision.

When an oceanic plate, which is dense and heavy, converges with a less dense continental plate, the oceanic plate is forced downward into the mantle in a process called subduction. This creates a deep ocean trench, like the Peru-Chile Trench, off the coast of South America. As the oceanic plate descends, it releases fluids that trigger melting in the overlying mantle wedge, generating magma. This magma rises through the continental crust, fueling chains of explosive andesitic volcanoes, such as the Andes Mountains or the Cascades. The collision and grinding of the plates also produce the world’s most powerful earthquakes.

When two continental plates collide, neither is dense enough to subduct significantly. Instead, the crust crumples and thickens, forcing vast sheets of rock upward to form towering, non-volcanic mountain ranges. The Himalayas, the highest mountains on Earth, are the direct result of the ongoing collision between the Indian and Eurasian Plates. The third type involves the convergence of two oceanic plates, where one subducts beneath the other, forming volcanic island arcs like Japan or the Aleutian Islands.

Transform Plate Boundaries

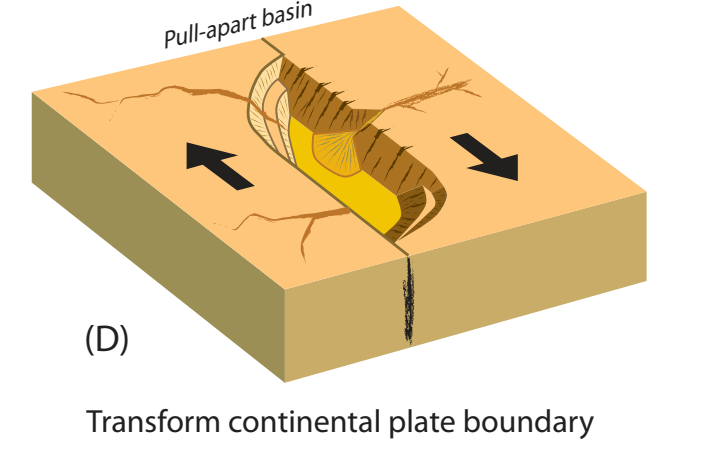

Transform plate boundaries, also known as conservative margins, are locations where two plates slide horizontally past one another. At these boundaries, lithosphere is neither created nor destroyed; it is merely conserved. The motion is not smooth, however. The plates grind and lock against each other due to friction until stress builds up to a critical point. When the stress overcomes the friction, the plates jerk past each other in a sudden, violent motion, generating powerful shallow-focus earthquakes.

The most famous example is the San Andreas Fault in California, where the Pacific Plate slides northward relative to the North American Plate. This boundary is not a single clean line but a complex network of faults that pose a significant seismic hazard to the region. Transform faults are also common along mid-ocean ridges, where they connect segments of the divergent boundary,accommodating the different rates of spreading.

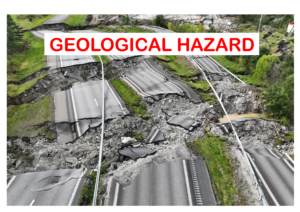

Role of Earthquakes and Volcanism

The movement and interaction at plate boundaries are the primary cause of earthquakes and volcanism worldwide. The vast majority of seismic and volcanic activity is concentrated along these dynamic margins. Earthquakes occur as the rocks strain and eventually fracture under the immense tectonic forces. Volcanism is directly linked to the melting of rock, which happens at divergent boundaries due to decompression and at convergent boundaries (specifically subduction zones) due to the addition of water from the sinking slab. Understanding plate tectonics allows geologists to map these hazard zones, providing crucial insights for risk assessment and disaster preparedness.

In conclusion, the theory of plate tectonics provides the essential framework for understanding the geology of our planet. The three main plate boundary types—divergent, convergent, and transform—are the active workshops where Earth’s crust is created, destroyed, and recycled. This grand, slow-motion cycle drives the continuous reshaping of our continents and ocean basins, fuels the planet’s most formidable geologic hazards like earthquakes and volcanism, and ultimately, makes Earth a dynamic and ever-changing world. By studying these processes, we not only unlock the history of our planet but also learn to navigate the challenges of living on its active surface.

Reference:

Klein, C., & Philpotts, A. (2017). Earth Materials: Introduction to Mineralogy and Petrology (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.